Today is the 20th anniversary of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone’s publication. Like many millions of others around the world, I love this book series. It is delightful. As are so many pieces of spin-off media, like the “Hogwarts Seminary” blog or the podcast “Witch, Please”, that draw continued fan engagement with the characters of the Harry Potter world. As my social media feeds ballooned with #HarryPotter20 celebrations today I came across an early interview with Joanne Rowling, the series’ author, in which she shares about her writing process and what the experience of seeing her first book in the book store was like.

Part of the interview discusses why the books are published under J.K. Rowling instead of Joanne Rowling. Here is a transcript of that answer:

Joanne: That was the publisher’s choice, rather than mine. I think they thought that J.K. Rowling was a more memorable name, but I think also because they thought it was a book that boys would enjoy. They might have wanted to hoodwink a few boys into thinking a man had written it.

Interviewer: Ah, I see.

Joanne: But I know that girls have really enjoyed it, from letters I have received.

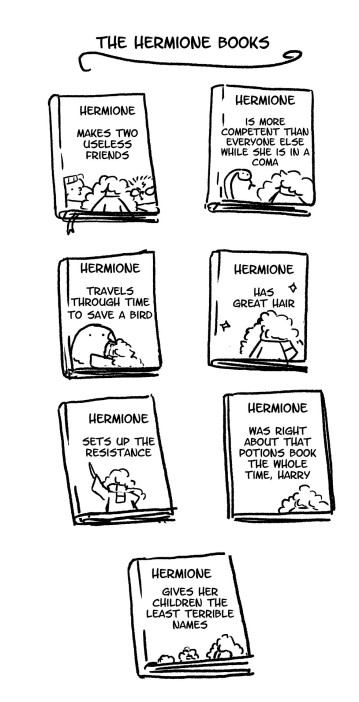

I have known this bit of trivia for a long time, but every time I hear it again it strikes me as significant. The assumption that boys (and young ones at that) would choose to avoid a book because a woman wrote it is sad, whether it was an accurate one or not. How quickly do young boys (and girls) internalize the idea that women are less worthwhile? Or that what women create is just for women and girls? Judging by the target demographic of the first Harry Potter book, the publishers believed that this process was complete by age ten. And, to add some conjecture, I suspect that if her name had been coded as “ethnic” she would have been prompted to whitewash her nom de plume as well.[1]

I struggle with how to evaluate Ms. Rowling’s decision to capitulate to her publishers’ wishes. As a then-undiscovered writer with little to no money, the power imbalance between her and her publishers was likely quite significant. She might not have been in a position to push back. Perhaps the memory of the multitude of rejection letters from previous publishers and the fact that she was a single mother living on social assistance meant she was willing to make any accommodations to our patriarchal culture needed to get her book (which no one knew at the time would become the phenomenon that it did) into as many tiny hands as possible. She accommodated and she benefited (richly).

Here is the rub: when an individual woman makes the decision to accommodate, she secures the benefits for herself (and others in her care) but her choices further the normalization of the conditions that make such accommodation necessary or beneficial. If Ms. Rowling had refused her publisher’s idea to de-feminize her name, would she have helped chip away at the publication industry’s assumption?

Whether it’s Ms. Rowling hiding her female-coded name, a server wearing a top that gets more tips, or nuns and abbesses submitting to the authority of a male abbot, there are many ways that women, past and present, navigate the stormy seas of male-dominated culture to their benefit – whether that benefit is financial stability, physical safety, or ease of social interaction. It is sometimes easy to judge other women for their capitulations to the patriarchy’s preferences, for not taking a stand and pushing back. If we hadn’t had women who fought back, (and queer people, and indigenous people, and people of colour, and immigrants, and, and, and…) the societal patterns and structures that reinforce straight, white, able-bodied, and male as the most valuable, “default” embodiment of human would never change. But is it fair of any of us to expect every woman in every circumstance to make herself a martyr?

What has this to do with theology (or, transliterated: What has Hogsmeade to do with Jerusalem)? Lots. As demonstrated in Jane’s recent post, theology as a discipline is not a place where women can assume they will thrive. It is another place where it helps to be able to hide behind initials. Ideally it wouldn’t be. As teachers of theology, we need to be cognizant of the probability that our male students and colleagues have not internalized that fact that what women have to say applies to them, could challenge them, or could make meaning for them. And we need to help them internalize it. We can do this by making sure that women’s voices (and other non-dominant voices, too) are included on each and every syllabus. We can make sure that we are citing women in our articles and conference papers. Let’s encourage men to read women’s work without them having to be “hoodwinked” into it. Perhaps, if we work together, we can push back against the “J.K. Factor” by ensuring a woman who publishes under her own name does not miss out on being taken seriously.

Accio justice!

[1] Every critique I include about gender power imbalances in this post also needs to be considered intersectionally. Ms. Rowling, like myself, can chose disguise herself easily with the use of initials. This expedient route to being taken seriously is not so readily available to others whose names are racialized.