(I think she looks a little too wry for someone being crushed by an unimaginable weight, but, hey—who can resist a snarky-looking saint?)

This is a long post—about twice the length of the papers my students recently wrote, in fact. But it’s about what sustains me through the difficulties of being a critical Catholic woman, and I hope it’s helpful to some of you.

Last week, April 29, was the feast of Catherine of Siena, one of the four women included in the list of theologian-saints whom the Catholic Church recognizes as Doctors of the Church. (If you haven’t already, be sure to check out these brief and inspiring words from M. Catherine Hilkert, Professor of Theology at the University Notre Dame). I’ve been thinking recently of her last reported mystical vision. Here’s how Paul VI relayed it in a general audience on April 30, 1969:

Weak, exhausted by fasting and illness, she came every day to St. Peter’s, the former basilica. In the porch there was a garden, on the facade a famous mosaic, painted by Giotto for the 1300 jubilee, and called the barque (now it appears inside the porch of the new basilica). It reproduced the scene of Peter’s boat, tossed by the night storm, and it represented the apostle daring to move towards Christ who has appeared walking on the waves; a symbol of life that is always in danger and always miraculously saved by the divine mysterious Master. One day, it was 29th January 1380, about Vesper time, Sexagesima Sunday, and it was Catherine’s last visit to St. Peter’s; it seemed to Catherine, caught up in ecstasy, that Jesus stepped out of the mosaic and came up to her, placing the barque on her weak shoulders; the heavy, storm-tossed barque of the Church; and Catherine, collapsing under the weight, fell to the ground unconscious. Historically, Catherine’s sacrifice seemed to fail. But who can say that burning love of hers disappeared in vain if myriads of virgin souls and hosts of priestly spirits and of faithful and industrious laymen, made it their own; and it still blazes in Catherine’s words: “Sweet Jesus, darling Jesus”?

Catherine spent her next three months in agony, dying on April 29 after a three-day paralysis. She was 33.

That image—the Doctor crushed by her church—has been swirling around my head, along with the question at the heart of this post: What is hope for the Church? I suspect that many readers of WIT have your own reasons sometimes to struggle to have hope for the Church (I’m speaking particularly to our Catholic readers, but, mutatis mutandis…). I know that I’ve got a few. And I don’t only mean “the Church” in the sense of narrow ecclesiologies (though the institutional hierarchy can be a particular challenge). There are times I struggle to have hope in all of us: times I feel profoundly alone, and in need of far more support than I’m getting for this Christian journey, and times (truthfully, not enough times) that I’m profoundly conscious of the ways in which I fail to offer that support and solidarity to others in any truly meaningful way—particularly but not exclusively as it relates to my benefitting from racism and failing adequately to protest US violations of human rights.

The ease with which we ignore one another’s pain forms the starkest denial imaginable of our claim to be one Body.

Now, for many Catholics I know, the election of Francis has made hope far easier to come by, and I’m not immune to that excitement. There are many hopeful signs, among them the report that the prefect of the Vatican Congregation for Religious now feels free to critique publicly some operations of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, while previously he “didn’t have the courage to speak” (“Obedience and authority must be renewed, re-visioned. … Authority that commands, kills. Obedience that becomes a copy of what the other person says, infantilizes”—that’s a Cardinal commenting on the effect of choices made by the CDF.) But I think that if any of us are going to keep talking about Francis inspiring “hope,” then we need a clarification of terms. Those who know me might know what’s coming next, because it’s a point that I’m hammering fairly consistently: hope is not optimism. In fact, in certain cases (I suspect most of the cases where it actually matters) optimism can be a vice opposed to hope. An optimist can discount and ignore evidence against her conviction that things will right themselves. An optimist is threatened by others’ pain. But someone acting in hope—the conviction not that things will right themselves, nor that we’ll be able to right them, but that God’s power will work to overturn whatever wrongs our systems can devise—that person can face pain. Without denying pain or being swept away by it, she can face her own and others’ suffering.

I have been excited by Francis’ pontificate, I recognize within myself a desire to protect that excitement (as Francis said in his inaugural homily, “Being protectors…also means keeping watch over our emotions, over our hearts”). But we don’t protect hope by shielding it from others’ pain—not even the pain of those we think probably just need to buck up and stop being so negative. As my very wise friend Fran Rossi Szpylczyn said (go check out her lovely blog!) to me about our shared and unexpected enamoration: “He’ll break our hearts, but he has captured them first, with love. Of course, what happens after they break will be most interesting. I suspect we are all in for many surprises.” That ability to admit that your heart will be broken, but to willing to learn what happens afterwards—that’s hope. We don’t protect hope by drawing in on ourselves and blocking others out; we protect hope by drawing closer to its source—and I’m enough of a Rahnerian to believe that there’s an ambiguity that makes that experience dark to ourselves. I’m enough of a Rahnerian, that is to say, to think that sometimes God’s Spirit is known “when despair is accepted and mysteriously experienced as assurance without any easy consolation” (“Experience of the Holy Spirit, TI 18).

Which brings me back to that image of Catherine and the barque of Peter. Paul VI draws our attention to the mosaic from which that barque emerges: Peter walking on water toward Jesus, “a symbol of life that is always in danger and always miraculously saved by the divine mysterious Master.” I’d like us to note the tensions in that image: Catherine is praying before a depiction of Jesus catching the sinking Peter and saving him from the stormy waters. But how is Jesus’ presence revealed to her? Not in similar fashion, not as someone who buoys her up and saves her from her fears—but as someone who lays Peter’s shelter on her shoulders as an agonizing weight, without even the consolation of seeing her pain bear fruit in the healing of the Church (and what an interesting gender contrast: Peter given shelter and comfort; Catherine given a painful burden). While I don’t claim this is an accurate description of Catherine’s life, focusing on the contrasts in this one image, I’m led back to Rahner (edited for gender):

Which brings me back to that image of Catherine and the barque of Peter. Paul VI draws our attention to the mosaic from which that barque emerges: Peter walking on water toward Jesus, “a symbol of life that is always in danger and always miraculously saved by the divine mysterious Master.” I’d like us to note the tensions in that image: Catherine is praying before a depiction of Jesus catching the sinking Peter and saving him from the stormy waters. But how is Jesus’ presence revealed to her? Not in similar fashion, not as someone who buoys her up and saves her from her fears—but as someone who lays Peter’s shelter on her shoulders as an agonizing weight, without even the consolation of seeing her pain bear fruit in the healing of the Church (and what an interesting gender contrast: Peter given shelter and comfort; Catherine given a painful burden). While I don’t claim this is an accurate description of Catherine’s life, focusing on the contrasts in this one image, I’m led back to Rahner (edited for gender):

Here is someone who is trying to love God, although there appears to be no response of love from God’s silent incomprehensibility, although she is not sustained by any feeling of enthusiasm, although she cannot confuse herself and her desire for life with God, although she thinks she will die of this love which seems to her like death and absolute rejection, which apparently calls her into the void and the wholly unknown: a love that looks like a terrifying leap into unfathomable depths, since everything seems to become intangible and utterly futile.

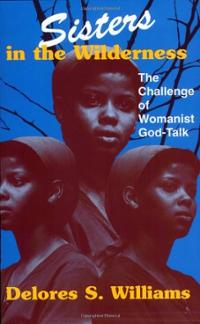

So what are we to do when our efforts to hope for the Church end up in “love which seems like death and absolute rejection”? I’m not offering a universal answer: I don’t think that’s possible or healthy. There are times people need to step (or walk) away, and part of facing one another’s pain is refusing to give in to the temptation to dismiss as narcissism or individualism what well may be a necessary act of spiritual self-care. But the theologian whom I, personally, most consistently find helpful in my own efforts to persevere in the Church is Delores Williams.

I’m deeply conscious of the danger of appropriating Williams’ work in a way that does violence to her own context and central concerns: Williams is a womanist theologian, and the ongoing racist oppression of black women is central to her work. When Williams talks about “survival” and “quality of life” (see below), she means these terms literally and concretely, in light of the ongoing manners in which white supremacy threatens the survival and flourishing of black women, children, and men. So when I say that her theology helps me live in the Church, the last thing I want to be saying is “Thank God the systematic violence, murder, and oppression of black people produces reflections that help me, a white woman, calm down when someone in the Catholic Church once again says that women will not be able to preach in mass!” But at the same time, I see it as a consistent problem in the theological academy that contextual theologies are confined to their contexts by white and/or Anglo and/or male and/or straight gatekeepers (see also this), rather than being received as genuine theology which should turn everyone’s attention to human realities in need of universal action with the power to reveal God.

So, what does Williams say is revealed about God?

Through a reading of the Hagar story informed by the experiences of black women in the United States, Williams develops a distinction between God’s action for human liberation, and God’s action for survival/quality of life. While Hagar acts courageously for her own liberation by running away from slavery and Sarai’s abuse, becoming “the first female in the Bible to liberate herself from oppressive power structures” (Sisters in the Wilderness 19), God’s intervention in Hagar’s life is not a liberating one. The angel of the Lord appears to Hagar, addresses her as “Hagar, slave-girl of Sarai,” and tells her, “Return to your mistress and submit to her” (Gen 16.9). Williams insists we reckon with the reality of the text: “The angel of Yahweh is, in this passage, no liberator God” (21). While God demonstrates concern for Hagar and her unborn son’s survival—no one can survive for very long in the wilderness without water, food, and shelter from the sun—”in this passage, God is not concerned with nor involved in liberation” (21).

Through a reading of the Hagar story informed by the experiences of black women in the United States, Williams develops a distinction between God’s action for human liberation, and God’s action for survival/quality of life. While Hagar acts courageously for her own liberation by running away from slavery and Sarai’s abuse, becoming “the first female in the Bible to liberate herself from oppressive power structures” (Sisters in the Wilderness 19), God’s intervention in Hagar’s life is not a liberating one. The angel of the Lord appears to Hagar, addresses her as “Hagar, slave-girl of Sarai,” and tells her, “Return to your mistress and submit to her” (Gen 16.9). Williams insists we reckon with the reality of the text: “The angel of Yahweh is, in this passage, no liberator God” (21). While God demonstrates concern for Hagar and her unborn son’s survival—no one can survive for very long in the wilderness without water, food, and shelter from the sun—”in this passage, God is not concerned with nor involved in liberation” (21).

The first time I read Williams’ Sisters in the Wilderness, I was profoundly disturbed by the centrality of this argument: shouldn’t we instead note that “God speaks in Sacred Scripture through men in human fashion,” as Dei Verbum puts it (Williams is Protestant, but the point stands), and attribute God’s non-liberating intervention in Hagar’s life to the human limitations and prejudices of the writer? But reflecting on my own experience in the years since I first read this text, I’ve become more and more convinced that Williams captures a reality that needs attention.

There are times that we’re not able to liberate ourselves and others. There are times we do need to endure unjust situations rather than striking the prophetic blow for justice we wish we could. There are times that our experience of living in a storm-tossed Church is not one in which God pulls us out of the waters and calms the wind—but one in which God lays the full, painful, crushing weight of that Church on our shoulders, and in which God’s presence does not alleviate that pain. If we conceive of God only as one who sustains the suffering, we absolutely risk turning faith into an analgesic, and active hope into passive optimism… but perhaps if we conceive of God only as one who liberates the oppressed, we leave ourselves with no way to engage in careful discernment and practice the virtue of prudence. It’s easy to condemn that as false or cowardly—until you’re in a situation where speaking up for yourself could seriously impede your ability to be effective later.

Williams does not interpret God’s acting for survival/quality of life as condemning Hagar’s own actions of self-liberation: God is with her in both the suffering and the freedom of the wilderness. Indeed, “Hagar is the only person in the Bible to whom is attributed the power of naming God” (23; emphasis added). Hagar rejects the way that God has been named by those who enslave and harm her, trusts the power of her own experience of a God who sees her and empowers her own sight, and names God El Roi, in “a strike against patriarchal power at its highest level” (26).

In the bible translation Williams uses, the meaning of the name El Roi is related to Hagar’s saying, “Did I not go on seeing here, after him who sees me?” In the NRSV, the explanation of this name focuses on Hagar’s amazement that she has seen God and lived: “‘Have I really seen God and remained alive after seeing him?”; the NAB version of Gen 16:13 translates El Roi: “To the LORD who spoke to her she gave a name, saying, “You are God who sees me”; she meant, “Have I really seen God and remained alive after he saw me?” To develop this story in accord with Williams’ interpretation, I think it’s appropriate to emphasize both the “sight” Hagar names in calling the LORD “God of seeing” and Hagar’s own sight which endures after their encounter. Not only has she survived; she has survived to “see.” Hagar survives and the validity of her own sight and self-interpretation is upheld.

While God does not liberate Hagar from injustice, God and Hagar together free her from seeing herself and God as Abram and Sarai see them. That’s a particularly important point to me in living the tension of feminist Catholicism. Williams further develops this point in her reading of Alice Walker’s The Color Purple: “As long as [Celie] lives in transcendent relation to her own experience, she is content to image God as male, old, and white. But when Shug helps Celie begin her process of self-discovery, Celie starts to understand that her notion of God must change, because ‘you have to git man off your eyeball before you can see anything a’tall.'”

So that’s what I’ve got. I don’t have optimism that anyone will transform all that I find excruciating and unbearable in the Church. But I have faith that God is present with all of us. And I have hope that God—and not, say, those who think this blog is written by a bunch of heretical radical feminists in states of mortal sin—is the one who sees me. And I am trying to persevere in the faith that God upholds my own sight.

Historically, Catherine’s sacrifice seemed to fail. But who can say that burning love of hers disappeared in vain if myriads of women and men made it their own; and it still blazes in Catherine’s words: “Sweet Jesus, darling Jesus”?

Thanks Bridget for a hopeful post which I found helpful.

A few years back we had a woman parishioner help give a dialog homily in our parish. I felt I’d seen the Kingdom come. The fascinating thing was that the woman who gave it was one of the most anti-feminist and most opposed to women speaking in Church !

On being crushed by the Church, in our formation we were taught to expect to be crucified. It’s perhaps helpful to remember that Christ was crucified by both Empire and Religion.

Venceremos.

God Bless

Your comment:

“I don’t have optimism that anyone will transform all that I find excruciating and unbearable in the Church”

reminded me that Vatican II taught the same:

Christ summons the Church to continual reformation as she sojourns here on earth. The Church is always in need of this, in so far as she is an institution of men here on earth. Thus if, in various times and circumstances, there have been deficiencies in moral conduct or in church discipline, or even in the way that church teaching has been formulated – to be carefully distinguished from the deposit of faith itself – these can and should be set right at the opportune moment.

Vatican II, DECREE ON ECUMENISM, UNITATIS REDINTEGRATIO, my emphasis

God Bless

Thanks Bridget. So much to think, and pray, with.