In 2011, I was asked to lead a women’s retreat in which attendants would come from divergent, and at times antithetical, walks of life. I knew there would be conservative, moderate and progressive women of various ages participating in this day of reflection. The theme for the day had yet to be determined and I was given no guidelines other than to address women’s spirituality. Accordingly, my preparation involved a great deal of wrestling with the question of how best to inspire and articulate meaning to a diverse group of women within my church. I desperately searched for a unifying theme and language to address all retreatants in this often polarized assembly. If I spoke of my spirituality in a solely traditional manner, I risked voicing an inauthentic understanding of God’s expression to me as a feminist-inspired woman of faith. On the other hand, I knew that if I used the “F” word, that is feminism, many in the audience would react negatively, tune me out and discontinue listening. After much prayer and reflection, I ultimately decided to heed the nudging I felt from God to trust my expression of and insights into women’s spirituality. Influenced by both traditional and feminist theology, I planned the entire retreat according to my inspiration and removed the “F” word from everything I presented. Essentially the content was feminist-inspired spirituality yet not once did I utter the aforementioned word.

To my surprise and delight, the retreat was enthusiastically received by all participants, as evidenced by their enthusiastic applause and conversation afterwards. They seemed hungry for the symbols, language and material that addressed them as women. Eagerly, I was invited to lead a follow-up retreat in the future. I was particularly moved by one of the most conservative retreatants present, who requested meeting with me privately to further delve into the material. She wished to share the ideas and symbols with her prayer group. This experience compelled me to consider feminist theology in a more nuanced way leaving me with many questions. Do the ideas and metaphors derived from a feminist theology appeal and speak to a broad spectrum of society? It seems clear that much of the content of feminist theology resonates with women from many walks of life. I wonder, however, if perhaps the word feminism and how it is sometimes presented has become problematic to some women. Has the word itself become a source of contention and division among the very population it was meant to influence and inspire? Our social media era communicates a broad confluence of ideas, perspectives and symbols on a daily basis to a wide range of people. After the retreat, I wondered, and continue to wonder, has the time come to reexamine usage of the “F” word in our post-modern theological lexicon?

For better or for worse, identification with the word feminism seems to be on the decline. In a 2013 HuffPost/YouGov Poll, only 20 percent of Americans, including 23 percent women- considered themselves feminists. However, when asked if they believe that “men and women should be social, political and economic equals” 82 percent of respondents indicated that they did. Interestingly, this is the precise full definition of feminism according to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary. It is clear that the principles of feminism remain important in today’s American culture. How can we understand this discrepancy?

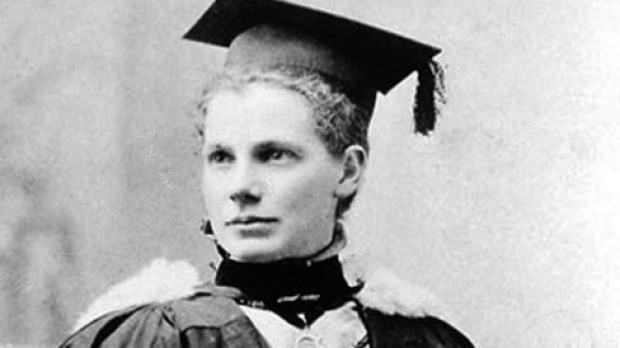

As a middle child living in the liminal space between the Baby Boom and Generation X  time periods, I empathize with the thought processes of both younger and older generations regarding feminism. Generations of women did not have the luxury of voting, owning property, possessing a credit card, earning a sustainable wage, attending a prestigious university or training in a profession beyond the jobs deemed acceptable for women, namely domestic labor, factory work, nursing or teaching. To be sure, our predecessors experienced sexism on a scale with which younger generations cannot identify or imagine. With a single-minded focus on breaking through unjust social barriers, the Baby Boom generation and some of our forbearers paved the way for all of us to afford the advantage of choosing how to express our options as women.

time periods, I empathize with the thought processes of both younger and older generations regarding feminism. Generations of women did not have the luxury of voting, owning property, possessing a credit card, earning a sustainable wage, attending a prestigious university or training in a profession beyond the jobs deemed acceptable for women, namely domestic labor, factory work, nursing or teaching. To be sure, our predecessors experienced sexism on a scale with which younger generations cannot identify or imagine. With a single-minded focus on breaking through unjust social barriers, the Baby Boom generation and some of our forbearers paved the way for all of us to afford the advantage of choosing how to express our options as women.

On the other hand, at least to some degree, Generation X and younger age groups assume certain freedoms already exist; these are given rights as human beings. The battle of the previous epoch simply does not pertain to them. It is not entirely accurate to say that younger women do not appreciate feminism. Rather, it may be the public characterization of this term that triggers a response in individuals. Whether fair or not, the “F” word is associated in some people’s minds with aggressiveness and a rather limited over-zealous agenda. Undeniably, feminism has been given a bad rap by some commentators and perhaps by some within the early movement itself. With provocative polarizing images of bra burners, men-haters, and feminazi’s, it is no wonder that when contemporary women wish to express a feminist viewpoint, they are often heard remarking, “I am no feminist but…

Undoubtedly, we are experiencing a shift in the cultural praxis and understanding of the “F” word. Many, including Martha Rampton observe that there are waves of feminism that have contributed to public thought and conversation over time. Though by no means fully realized, have some of the intentions of the feminist movement begun to settle into our current sensibilities? Is feminism evolving in a way that is transforming our discussions about it? Too often in the past, conversations involving feminism, including feminist spirituality, have taken place apart from the mainstream, mentioned only among like-minded individuals. Have we come to a place in time when we are beginning to speak of feminist principles using language that unifies and inspires communication? When it comes down to it, the name we assign our theories pales in comparison to elucidation of these thoughts and ideas.

To be sure, feminist spirituality can mean different things to different people. For women writing in theology, feminist theology in its purest form simply means expression of our relationship to God from a woman’s perspective. Over the centuries, men primarily interpreted and handed down theology which made sense considering the prevailing culture and time period. There is beauty, truth and inspiration in much of this. However, the equally valid question remains, how do women express God and how does God express Godself to women? We have arrived at a time in our consciousness when the doors are opening for women to address these questions. As we read in Genesis 1:27, both male and female are equally made in the image of the Divine. Because being human means being a man or a woman, there is necessarily a dialectical nature inherent in creation. In order for theology to reach its fullest expression, it must hear from both persons of the human.

For all its imperfections and battle-scars, it must be recognized that feminism has gifted our spirituality and left an indelible impression upon our faith expression. What are some of the gifts that feminism has brought to theology?

- Strength– Here, I mean strength in the sense of women recognizing the value of their own voice and perspective. Our strength comes not in militancy but rather in understanding that as a woman, we have something valuable and necessary in the theological conversation.

- Inclusivity-There is no single perspective in the theological discussion. Instead, there is a developing realization that many voices are necessary, including the masculine and feminine, to create and develop a more complete understanding of faith.

- Co-imagination- Most theology from the past recorded only men’s interpretation and imagination when posing doctrine and assigning meaning. Jesus departed from his patriarchal culture by repeatedly listening to women’s stories. Reflecting from a woman’s perspective on Jesus’ actions adds fresh insight and contributes meaning to theology.

- Heterogeneity- There is recognition that there are some differences between men and women. These differences are equally valuable and important. A woman’s focus, sensibilities, perspective and worldview is different to a certain degree from a man’s. Each have unique contributions towards a balanced theological picture.

- Reciprocity-While differences exist between men and women, there is growing appreciation that these differences are not meant to be kept in a closed system exclusively for men or women separately. The back and forth dialogue between men and women builds up, challenges and is healthy in the theological discussion. A sense of mutual responsibility exists when we both give and receive thoughts and ideas from one another.

Here is my question: can we respect feminism without self-identification with this title? Can we engage and remain in discussion about the gift of feminism? Do we need to use the “F” word today in order to allow balanced expression of the feminine and masculine in theology? I leave these questions to each reader’s discretion and his or her own reflective process. Ultimately, what matters most are the ideas we convey, the respect we give and are given, and the ability to add our voice to the conversation. The life of Jesus inspires me in light of these questions. He did not preach an explicit doctrine either for or against feminism, yet his actions, words and ideas were clearly feminist. He broke with tradition by addressing women, lifting them up, encouraging them to follow him and tell their stories, and proclaiming that the Reign of God was for them too. He boldly lived his convictions emphasizing the meaning behind everything he said and did. How do you express God and how does God express Godself to you?

My faith was revolutionized by Letty Russell’s book, Human Liberation from a Feminist Perspective. She looks at Jesus Christ as God’s Word about our (equal) call to service.

That is one I have not yet read. Thank you- I look forward to reading it.

As I read your post, I have deep sympathies. Your theology is rooted in God’s Word, but as you attempt to label it, someone else tries to impress their own label upon YOUR label. Keep pressing on. Keep praying. Keep loving others.

I am able to empathize also because whenever I try to identify myself as an “Evangelical,” so many hear “Fundamentalist.” I could point everyone who to Carl Henry’s books, and show them their error in definition, but it will only cause argumentation. Instead, I shy away from labeling my own theology and let those who want to call it “liberal” call it “liberal;” and those who call my theology “conservative” I will let them call it that.

We can only do so much to control how people understand labels. Instead, as we show others love and compassion, we pray that they know us by our love, and forget labeling.

And, once again, great post!