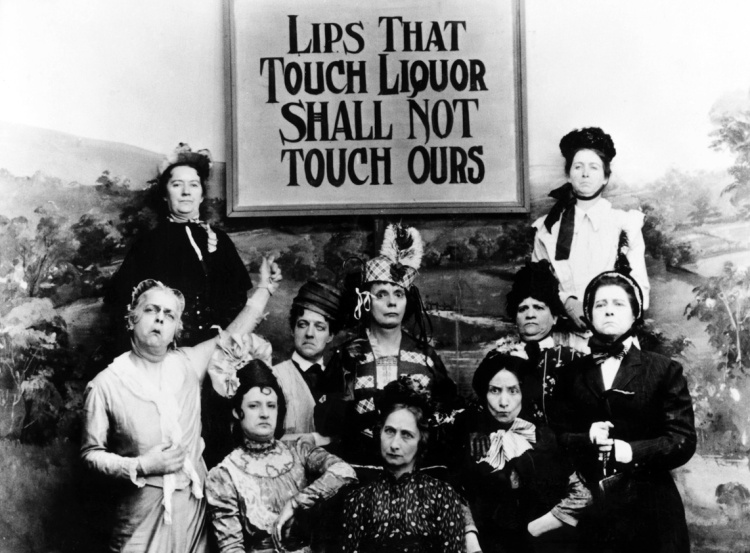

In the first year of my PhD studies in the History of Christianity, I found myself researching early twentieth-century feminist activists. A coursework research paper drew me to focus on the Ontario chapter of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). By the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 the Ontario WCTU could boast roughly 10,000 members in nearly 550 local unions.[1] One monthly newsletter correspondent gives us a sense of the variety of issues with which the WCTU was involved:

[We are fighting] battles against rum and nicotine and impurity; against inborn criminality and sweatshops and gambling and tenement poverty; against a double standard of purity and wasted resources and desecration of the Lord’s day; against missionary whisky and polygamy, and slums, and spoils of office and base partisanship and active ignorance. [2]

A many sided effort! The women in the WCTU, my supervisor later pointed out to me, were given the alternate moniker “Women Constantly Tormenting Us” by men who found the ladies’ virtually omnipresent advocacy work put a damper on typical leisurely pursuits.

As I delved into the world of the WCTU, my critical ‘third wave’ feminist lenses were both helpful and hindering. As a ‘third-waver’, I had fully absorbed a particular caricature of ‘first wave’ feminism and the women that propagated it – white, upper-middle class, prudish, gender-essentialist, maternal, too narrowly focused on “The Vote”, and (in my Canadian context) too dedicated to a certain sense of British racial superiority and too uncritically loyal to the Imperial cause. While I could clearly see elements of the ‘first wave’ caricature amongst the WCTU, I also saw much more. These women possessed a certain gumption and confidence (albeit with a healthy dose of idealistic naiveté) I found captivating. My admiration created some internal tension. Was my fondness a betrayal of my critical ‘third wave’ lenses?

Later on, as I read Nancy Hewitt’s No Permanent Waves: Recasting Histories of U.S. Feminism, I understood what lay at the heart of the tension: I had internalised a flawed historical narrative when it came to Canadian (and American) feminism. My understanding of that narrative had been ill-shaped by the very metaphor we often use to describe it: waves of feminism. Hewitt calls into question the appropriateness of the wave metaphor so prominent in discussions of feminist history. Given the complexity of “movements for women’s advancement and liberation,” the metaphor is limiting in Hewitt’s view because “the concept of waves surging and receding cannot fully capture these multiple and overlapping movements, chronologies, issues and sites.”[3]

Thinking in ‘waves’ has led to the development of a thoroughly presentist attitude amongst many feminists. Each subsequent ‘wave’ has been critical of a perceived narrowness in their predecessors’ vision and has considered themselves a bigger, better, more aware version of ‘feminist.’ These movements end up being defined by their (real or imagined) contrasts rather than their continuities and, seeking to reinforce these contrasts, the newer ‘waves’ end up mischaracterizing those that preceded them.

Thinking in ‘waves’ has led to the development of a thoroughly presentist attitude amongst many feminists. Each subsequent ‘wave’ has been critical of a perceived narrowness in their predecessors’ vision and has considered themselves a bigger, better, more aware version of ‘feminist.’ These movements end up being defined by their (real or imagined) contrasts rather than their continuities and, seeking to reinforce these contrasts, the newer ‘waves’ end up mischaracterizing those that preceded them.

My ‘first wave’ caricatures were a textbook case of the mischaracterization Hewitt looks to undermine. These ‘first wave’ women had enormous vision – vision informed by economic realities, prejudices, and assumptions of the day, certainly. But small scale or narrow vision it was not. Hewitt’s arguments helped me repent of my presentist sins. Rather than be disappointed that women of the WCTU had not rallied against the gender-essentialism of the era, I admired they way they reworked rhetoric about the duties of Christian womanhood and the vocational calling of motherhood. These restrictive cultural constructs became tools used to legitimize women’s advocacy work and desire for social reforms.

I do not seek to promote members of the WCTU as perfect heroines. But I am exceptionally grateful for them. While many of their dreams went unrealised, their efforts had a significant impact on the religious and political landscape I inherited a few generations later. Their narratives have complicated and interrupted my own and, for that, am grateful to have encountered their stories.

I am also grateful for Hewitt’s critiques. One might question whether it is feasible to abandon the ‘waves’ metaphor when it is so widely used. Hewitt suggests it might be most helpful, rather than jettisoning the image altogether, to consider waves differently – as radio waves rather than ocean currents. She explains the potential that might be unlocked if we readapt the existing metaphor to better suit our purposes:

Radio waves allow us to think about movements of different lengths and frequencies; movements that grow louder or fade out, that reach vast audiences across oceans or only a few listeners in a local area; movements that are marked by static interruptions or frequent changes of channels; and suddenly come in loud and clear. … Best of all, radio waves do not supersede each other. Rather, signals coexist, overlap, and intersect. [5]

Radio waves allow us to think about movements of different lengths and frequencies; movements that grow louder or fade out, that reach vast audiences across oceans or only a few listeners in a local area; movements that are marked by static interruptions or frequent changes of channels; and suddenly come in loud and clear. … Best of all, radio waves do not supersede each other. Rather, signals coexist, overlap, and intersect. [5]

Recasting accepted terminology in a more constructive framework is exceptionally helpful. Hewitt’s problematizing of the wave metaphor gives us greater flexibility with our historical narratives. As you consider the stories you tell about women’s movements toward liberation, how ‘wave’-informed are they? How do you consider the relationship between the feminist work of today and that which came before?