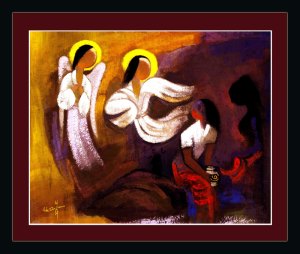

As Elizabeth mentioned in her first post on Mariology, I find much Marian piety rather difficult to appreciate, for various reasons (feminist, christological, ecumenical, historical-critical). Despite that, I often find myself quite moved by artistic portrayals of the Annunciation, both visual and poetic.

My favorite painting of the Annunciation, without question, is Henry Ossawa Tanner‘s (1898). Tanner, the first African American artist to have his work displayed in the White House, traveled twice to the Middle East and modeled his paintings of biblical themes on the people and buildings he saw there. Tanner’s Mary is young, and has both a quiet solemnity and an uncertainty, and looks as though she’s been woken in the middle of the night.

My favorite poetic reflection on the Annunciation is Denise Levertov‘s. While my theological commitments and, perhaps, own life of faith lead me to question whether graced moments ever disappear when refused–in my experience, God is far more persistent than that–there is something painfully, achingly beautiful in the lines:

Aren’t there annunciations of one sort or another in most lives? Some unwillingly undertake great destinies,

enact them in sullen pride, uncomprehending.

More often those moments

when roads of light and storm

open from darkness in a man or woman,

are turned away from in dread,

in a wave of weakness,

in despair and with relief.

Ordinary lives continue.

God does not smite them.

But the gates close, the pathway vanishes.

and the part of me that would like to see non-patriarchal and theologically sound interpretations of Mary appreciates Levertov’s often-omitted final stanza:

She did not cry, “I cannot,

I am not worthy,”

nor “I have not the strength.”

She did not submit with gritted teeth, raging, coerced.

Bravest of all humans,

consent illumined her.

The room filled with its light, the lily glowed in it,

and the iridescent wings.

Consent,

courage unparalleled,

opened her utterly

…though less for its reflections on the immediate context (that being, well, the annunciation…) than for the deep and hard truth of discipleship requiring from us something so much harder than insistence upon our lack of worth or worthiness. I love, too, that the central word here is consent, not submission.

But I’m going to end with an artistic work I feel a bit more ambivalently toward–an excerpt from WH Auden’s “For the Time Being: A Christmas Oratorio,” which, honestly, I have always loved. (For a not-entirely-complete but still impressive reading of this long poem, see WYNC.) Auden’s poem offers a reinterpretation of nearly every moment of the traditional “Christmas story” — the magi are disillusioned philosophers and scientists, the shepherds are workers, and Herod’s prose soliloquy is a rather stunning exposé of the sort of bourgeois-reasoning-cloaked-as-Christianity that we are all all too familiar with, and a reminder of how frighteningly radical this Advent of the non-emperor should be.

When re-reading this segment of the poem this year, I am uncomfortably aware of the disjunct between the rapid consumption-based happiness of The! Christmas! Season! and the far less comforting notion of awaiting the Second Coming… My own Christmas countdown has been haunted by Amos this year: Alas for you, Bridget, who desire the Day of the Lord! Why do you want the day of the Lord? It is darkness, not light — particularly for those who oppress the poor and the immigrant (do I need to list the material for a national Advent examination-of-conscience on these fronts?… ) I’m reminded as well of the truly mind-boggling irony at play in Jonah Goldberg citing Herod’s speech as a frightening foretaste of what will come should the US respond to its new experience of vulnerability with anything other than military force (and again a year later as part of a general attack on the “Left”) : to take grief seriously is to open the door to that world feared by Herod in which

Justice will be replaced by Pity as the cardinal human virtue, and all fear of retribution will vanish. … Every crook will argue “I like committing crimes. God likes forgiving them. Really the world is admirably arranged.” … The New Aristocracy will consist exclusively of hermits, bums, and permanent invalids. The Rough Diamond, the Consumptive Whore, the bandit who is good to his mother, the epileptic girl who has a way with animals will be the heroes and heroines of the New Tragedy when the general, the statesman, and the philosopher have become the butt of every farce and satire.

Naturally this cannot be allowed to happen. Civilisation must be saved even if this means sending for the military, as I suppose it does. How dreary. … (see Auden’s Collected Poems, 393-94)

Alas for we who desire the Day of the Lord, indeed!

But let us return to the Annunciation–or, more precisely, to the curious birth of the Lord, as it’s Auden’s treatment of Joseph to which I find myself returning. Auden gives us Joseph at the bar, tormented by the whisperings of the crowd (Mary may be pure, / But, Joseph, are you sure? / How is one to tell? / Suppose, for instance . . . Well . . . ), followed by a dialogue between Joseph and Gabriel, prompted by Joseph’s anguished cry to God for proof of Mary’s virtue.

This is not the Matthean Joseph, given angelic assurance of Mary’s virtue and divinely encouraged to take her as his wife without fear. Auden’s Joseph is a man consumed with uncertainty, who genuinely wants to believe Mary–but like so many of us, wants God to make this risky trust easier, to give him certainty and silence the whispering voices within and outside his head:

All I ask is one

Important and elegant proof

That what my Love had done

Was really at your will

And that your will is Love.

Gabriel responds to Joseph: “No, you must believe; / Be silent, and sit still.”

To us, though, Auden offers a lengthier explanation: Joseph is given no certainty as a sort of balancing of the scales for various instances of male privilege. I’m going to include this poem-within-the-poem in its entirety below, but before that I want to say that I am never quite sure what to make of this: the first time I read it, in high school, I was thrilled: “To-day the roles are altered; you must be / The Weaker Sex whose passion is passivity.” Today I’m less certain that I want to embrace this mid-century portrayal of gender, less certain it isn’t more problematic than I thought as a teenager, for all sorts of reasons.

Each time I read it, actually, I have this internal tug-of-war —it’s beautiful! it’s problematic! it’s insightful! it re-inscribes! But to end with one final thought, as I re-read “The Temptation of St. Joseph” this year, it struck me that Christian reflection on the trustworthiness of the utterly unbelievable reports from a woman don’t center solely on such poetic reflections on the birth narratives:

“Moreover, some women of our group astounded us…” Auden’s imaginative construction of Joseph’s doubt, his desire to ground his life in more than a woman’s testimony to some ridiculous and unbelievable claim forms a lovely inclusio with the challenge that that connects Jesus’ ministry to the faith life of the Church.

The off-stage chorus’ lingering doubts address us, too, concerning the claim of our faith first preached by another Mary.

Joseph, you have heard

What Mary says occurred;

Yes, it may be so.

Is it likely? No.

from “The Temptation of St. Joseph,”

For the Time Being: A Christmas Oratorio,

by WH Auden

(for those who preefer to hear this poem, this segment starts at 27:40 in the Green Space reading)

For the perpetual excuse

Of Adam for his fall–“My little Eve,

God bless her, did beguile me and I ate,”

For his insistence on a nurse,

All service, breast, and lap, for giving Fate

Feminine gender to make girls believe

That they can save him, you must now atone,

Joseph, in silence and alone;

While she who loves you makes you shake with fright,

Your love for her must tuck you up and kiss good night.

For likening Love to war, for all

The pay-off lines of limericks in which

The weak resentful bar-fly shows his sting,

For talking of their spiritual

Beauty to chorus-girls, for flattering

The features of old gorgons who are rich,

For the impudent grin and Irish charm

That hides a cold will to do harm,

To-day the roles are altered; you must be

The Weaker Sex whose passion is passivity.

For all those delicious memories

Cigars and sips of brandy can restore

To old dried boys, for gallantry that scrawls

In idolatrous detail and size

A symbol of aggression on toilet walls,

For having reasoned–“Woman is naturally pure

Since she has no moustache,” for having said,

“No woman has a business head,”

You must learn now that masculinity,

To Nature, is a non-essential luxury.

Lest, finding it impossible

To judge its object now or throatily

Forgive it as eternal God forgives,

Lust, tempted by this miracle

To more ingenious evil, should contrive

A heathen fetish from Virginity

To soothe the spiritual petulance

Of worn-out rakes and maiden aunts,

Forgetting nothing and believing all,

You must behave as if this were not strange at all.

Without a change in look or word,

You both must act exactly as before;

Joseph and Mary shall be man and wife

Just as if nothing had occurred.

There is one World of Nature and one Life;

Sin fractures the Vision, not the Fact; for

The Exceptional is always usual

And the Usual exceptional.

To choose what is difficult all one’s days

As if it were easy, that is faith. Joseph, praise.

Thanks for posting part of the poem. I’d not heard of it before. I like annunciation art too, especially the pre-raphaelites ones by Burne-Jones, Waterhouse, and Rossetti.

Many thanks for this post, Bridget. This Advent I’ve returned several times to this blog to see that Tanner painting. It’s captivating, not just because it’s really well done (I don’t have the vocabulary for this, since “I don’t know art but I know what I like”) but more because it’s a contrast between Mary’s experience of waiting and ours. We have all the benefits of knowing the end of the story and possessing this narrative distance that Mary didn’t have, and Tanner really brings out the dignity that Mary shores up in the face of uncertainty. It’s really great!

You may like to take a look at the sketch made by Rembrandt of the Annunciation. He never painted the biblical scene, however the sketch is quite telling. Mary has turned her face away from the angel, as if in fright, and has fallen from her chair. Surprise, surprise at the visit from an angel!